Protective Coating Could Prevent Pipeline Clogging

TUESDAY, APRIL 25, 2017

Hoping to prevent another disaster on the scale of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig catastrophe, Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers have unveiled a solution that could prevent blockages inside oil and gas pipelines and, more importantly, eliminate pipeline ruptures that result from pressure buildup.

Researchers in @mitmeche have designed a new coating to prevent pipeline clogging https://t.co/OyU9DqLQ8I pic.twitter.com/w3CFYPopck

— MIT (@MIT) April 14, 2017

The new method of preventing icy buildup is described in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, in a new paper by associate professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi, postdoc Arindam Das, and recent MIT graduates Taylor Farnham and Srinivas Bengaluru Subramanyam.

The research was funded by the Italian energy company Eni S.p.A. through the MIT Energy Initiative.

Measures Needed

The explosion and blowout at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig occurred on April 21, 2010. It led to the worst oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry—210 million gallons of oil leaked into the Gulf of Mexico—and 11 crewmembers were killed.

Despite their best efforts, the well’s operators couldn’t successfully block the leak. On May 9, 2010, they lowered a 125-ton containment dome over the broken wellhead. The measure failed: Instead of funneling the leaking oil into a pipe that carried it to a tanker ship above, it continued to drain into the Gulf of Mexico.

Finding the Cause

The culprit? An icy mixture of frozen water and methane, called a methane clathrate. Low temperatures and high pressure near the seafloor caused a slushy mix build up inside the containment dome and block the outlet pipe. That prevented the flow from being redirected.

|

| MIT research |

|

A technique devised by MIT researchers coats the inside of the pipe with a layer of a material that promotes spreading of a water-barrier layer along the pipe’s inner surface. This layer has proven effective in preventing the adhesion of ice particles or water droplets to the wall. This method halts the buildup of clathrates that could slow or block the flow. |

The MIT scientists determined that if not for the methane clathrate, the containment dome possibly might have worked. Four months of nonstop leakage and the widespread ecological devastation that ensued might have been prevented.

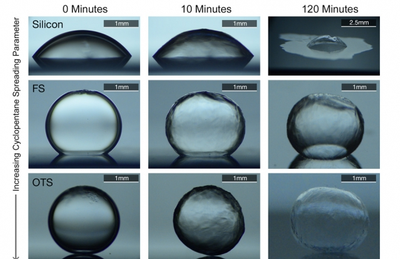

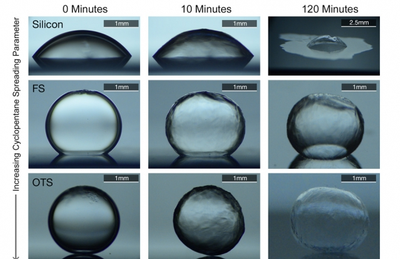

According to MIT, the key to the new system is coating the inside of the pipe with a layer of a material that promotes spreading of a water-barrier layer along the pipe’s inner surface. This layer has proven effective in preventing the adhesion of ice particles or water droplets to the wall. This method halts the buildup of clathrates that could slow or block the flow.

‘A Passive Method’

As in what happened at Deepwater, the key is to prevent ices from attaching to the walls of the pipeline. After determining heating pipe walls, depressurizing or using expensive chemicals that were also pollutants failed to pass muster, researchers settled on a passive method—creating a thin surface layer that repels water and prevents ice from adhering to the pipe’s walls.

Without those new measures, Varanasi notes that when hydrates build up they reduce the flow rate—which reduces revenues—and if they create blockages, that “can lead to catastrophic failure. It’s a major problem for the industry, for both safety and reliability.”

Das, the paper’s lead author, explains that the problem could be exacerbated because methane hydrates are viewed as a new potential fuel source if methods are devised to extract them.

“The reserves themselves substantially overshadow all known reserves [of oil and natural gas] on land and in deep water,” Das says.

Farnham says preventing these icy buildups depends on stopping the initial particles of clathrate from adhering to the pipe.

“Once they attach, they attract other particles” of clathrate, and the buildup takes off rapidly, Farnham adds. “We wanted to see how we could minimize the initial adhesion on the pipe walls.”

Citing Precedent

The approach to solving the pipeline dilemma has its roots in work Varanasi did for his company, which was established to commercialize earlier work from his lab. The firm creates coatings for containers that prevent the contents— including ketchup, honey, paint and agrochemicals—from sticking to container walls.

Varanasi’s lab developed a two-step system: apply a textured coating on the container walls, and then add a lubricant that gets trapped by the texture and prevents its contents from adhering.

Varanasi points out that the new pipeline system devised by MIT researchers is similar to his aforementioned lab work. The one difference, he notes, is “we are using the liquid that’s in the environment itself,” rather than applying a lubricant to the surface. Get the water away from the pipe wall, he says, and clathrate buildup can be stopped.

|

| U.S. Department of Energy |

|

The Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico sent 210,000,000 million gallons of oil spewing into the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010. |

“If the oil (in the pipeline) is made to spread more readily on the surface, then it forms a barrier film between the water and the wall,” Varanasi adds.

The researchers used a proxy chemical for methane; actual methane clathrates form only under high-pressure conditions, which are difficult to reproduce in a lab. But, tests of the system were highly effective, the scientists say.

“We didn’t see any hydrates adhering to the substrates,” Varanasi says.

Tagged categories: Coating chemistry; Coating Materials; Industrial coatings; Oil and Gas; Pipelines